The Unquiet Man

"I know what you're going to do," director Richard Lester told actor Oliver Reed before a take, "You're going to whisper three lines and shout the fourth." And indeed, Reed, nephew of the esteemed filmmaker Carol (The Third Man) Reed, would boast of being "the sound man's enemy" due to his unpredictable delivery: because sometimes, in fact, it might be the third, or second, or first line that got shouted.

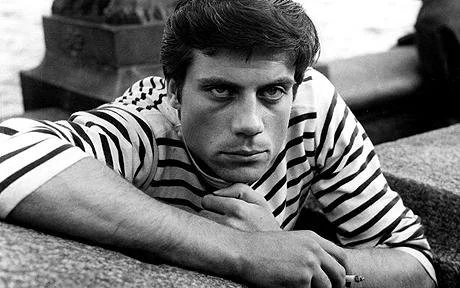

While in the case of a Branagh or a Hopkins, such random show-off vocals can be a sign of over-eager pursuit of spurious "energy" or a bored old barnstormer amusing himself, the effect with Reed was to enhance his palpable aura of danger, a combination of what is known as brooding intensity with a whiff of suspected lunacy, psychopathy or outright lycanthropy (Reed was British cinema's second wolfman in Curse of the Werewolf (1961).

For Lester, Reed was a glowering Athos in three Musketeers films (1973, 84, 89), and a glowering Bismarck in Royal Flash (1975). He appeared multiple times for another idiosyncratic genius of the UK cinema, Ken Russell, most famously in The Devils. Lester reckons Russell alone was capable of getting the intimidating Reed to vary his schtick, "because they were the same, in a way."

In what way? Both Russell and Reed were fond of a drink, though Russell leaned towards wine ("Better before lunch," was the Devils props man's verdict on his director, in a discussion with me decades later) and Reed was a beer man (106 pints over two days as preparation for his third marriage in 1985). Russell seems to have been slightly alarmed by his leading man's rambunctious behavior on Women in Love (1969), when Reed threw himself on the bonnet of Russell's moving car to initiate a discussion about his character, but in fairness Russell caused Reed some anxiety with the British cinema's first and most celebrated frontal male nudity scene (Reed wrestles an equally nude Alan Bates before a roaring fire).

"He wasn't the best actor in the world," Russell said of Reed, but he cast him repeatedly because Reed had the kind of star quality rare in Britain: raw, uncivilized, intimidating. Michael Caine and Richard Burton could do good explosive rage, but Reed projected a far more intense feeling of being about to rip one's head off. He supplied a usefully serious, low-key and butch quality to Russell's increasingly camp, flamboyant TV and film work.

Reed's vocal gymnastics would have caused the sound man less trouble in the case of Damiano Damiani's Revolver (1973), since in the manner of most Italian cinema it's all post-dubbed. It's a politiziotteschi, an Italian cop film, which have, arguably, two main strains: the Dirty Harry thick-ear proto-fascist romp, and the cynical leftist social critique. Revolver is the latter type, and though one can imagine Reed, macho man that he was, having a whale of a time in Harry Callahan terrain, it's always good to see him in something more respectable (he made a lot of shit films).

For reasons best known to himself, Reed plays Milanese Inspector Vito Cipriani with the worst American accent on record, a revenge perhaps for Dick Van Dyke's legendary Cockney in Mary Poppins. That bad. A shame, but you get used to it, and the film showcases everything interesting about Reed, his capacity for terrifying rage ("I'm gonna turn this town inside out like a fuckin' sock!"), his surprising moments of sensitivity (the plot revolves around his quest to rescue his kidnapped wife), and his simmering, Romantic, murderous potency, radiating out of his eyes like atomic decay of the soul.

We shall not see his like again. "Not the best actor in the world"? Lester, and trashmeister Michael Winner, who also used Reed a lot, would agree. But I admire him the more for getting all his effects with such limited means, for never being emotionally unconvincing. Pretty much an embodiment of toxic masculinity (fired from 1995's Cutthroat Island for turning up wrecked and exposing himself to the star) he could somehow turn that into tortured humanity. Do we need that today? Probably, because the male monsters haven't gone away, and drama would prefer them to be more complex than otherwise.

by David Cairns