The Gaze of the Glass

Jean Epstein

[translated by Keith Sanborn]

The French original was first published in a magazine called Les Cahiers du mois, no 16-17, 1925. It was republished in part in Le cinématographe vu de L’Etna, ch. 1. As far as can be determined, this is the first complete English translation.

…But I do not mean, that one must work in the cinema according to theories, neither these, nor others. The symphonies of movement, which have come into fashion too late, are now quite tedious. Caligarism only offers photographs by painters, which are neither better, nor worse than those of the Salon des Artistes français. The “pompier”* style appears whenever invention ceases, in cubism as in “rapid” montage, or in this sort of cinematographic subjectivism which, by force of superimpositions, becomes ridiculous. One can only write, if one feels and thinks oneself. I would like to approach each of my films as this traveler [does] his train, who arrives at the station only at the next-to-the-last minute, but still with six trunks to check, his ticket to pick up, and his seat to find. He departs, but does he know for where? The grace of God is his only time table without accidents. He arrives in the fatherland of surprises. That’s the country they had promised us.

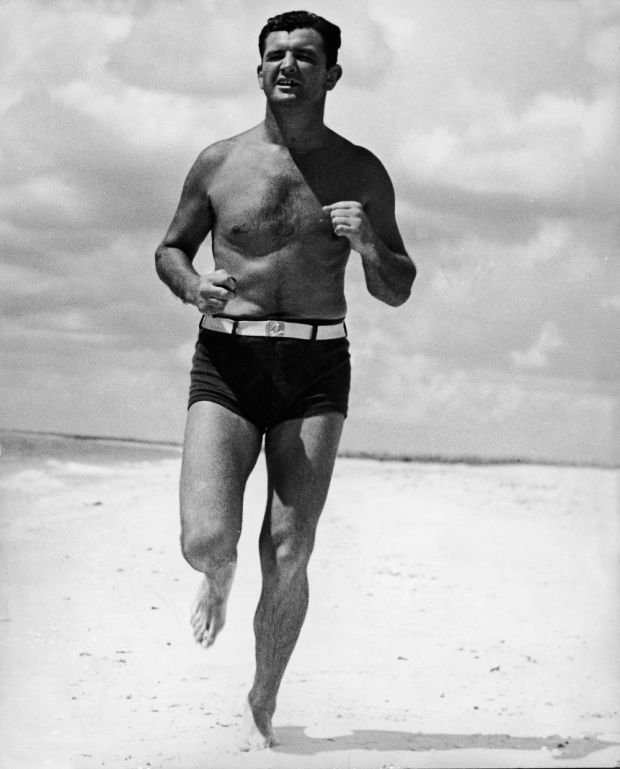

Cinderella Men

Baseball, boxing and horseracing were the most popular sports in Depression America. All three offered plucky underdogs and Cinderella stories to distract people from their own troubles. While the Yankees were winning the Series with monotonous regularity, the scrappy, often hapless Dodgers had more, and more devoted, fans. When the smaller Seabiscuit outran the mighty War Admiral; when Jimmy Braddock made his amazing comeback; when Joe Louis knocked down Hitler’s superman, it gave you a sense that you might come out all right yourself.

James Braddock’s story was ready-made for the era. He was born in a Hell’s Kitchen tenement in 1905; the following year, his poor Anglo-Irish immigrant parents moved their large family across the Hudson to New Jersey. He started boxing late, at 18, a fighter of tremendous heart and moxie, but bad hands. In 1928, three years into a very promising professional career, he broke his right in two successive fights, and would break it again later. His career slid, until by 1933 “he had gone from headline to breadline,” as biographer Michael C. DeLisa put it. He was taking what work he could get as a longshoreman on the Weehawken docks and accepting $6.40 a week from a New Jersey relief agency to feed his kids.

Banking on Hitler

Between World War I and World War II, Wall Street’s big banks invested heavily in Germany’s recovery. As early as the Versailles treaty negotiations, an American team led by Wall Streeters Bernard Baruch, John Foster Dulles, and J. P. Morgan’s Thomas W. Lamont argued without much success against forcing Germany to pay the punitive reparations demanded by the other allies. In political and financial chaos, Germany was failing to keep up the payments within a year, and in 1923 France and Belgium occupied Germany’s industrial Ruhr as a way to extract the funds directly. Lamont led the renegotiation of the reparation payment schedule, and organized other giant Wall Street banks to bail Germany out with loans.

He also participated, with other New York bankers, in setting up the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in Basel, Switzerland, in 1930, ostensibly to facilitate the reparation payments. The BIS was the brainchild of Hjalmar Horace Greeley Schacht, who in a few years would become Hitler’s president of the Reichsbank and Economics Minister. Schacht came into his unusual middle name because his father, as a German immigrant to New York City shortly after the Civil War, idolized the liberal newspaperman Greeley. Hjalmar was conceived in New York, but born in Germany.

The BIS was (and remains today) so low-profile as to be nearly invisible, the Swiss bank to end all Swiss banks, without even a sign on its nondescript building in Basel. Its partners included the Reichsbank, the Bank of England and other European central banks, Japan’s central bank, and three Morgan banks: J. P. Morgan and the Morgan-affiliated First National Bank of New York and First National Bank of Chicago. When Schacht stopped Germany’s reparation payments in 1932, citing the world depression, the BIS sailed on, pursuing its real goal: to be a safe and discreet clearinghouse that would allow all those banks to continue doing business together, despite whatever their respective nations were doing, even if that included war. Via the BIS, the American and British bankers would maintain a mostly secret friendship with their Nazi and Japanese counterparts straight through World War II, while thousands of American and British men in uniform were being killed and maimed in the fight to defeat the Nazis and Japanese.

Throughout the war, the BIS would shelter hundreds of millions of dollars in Nazi gold, stolen from conquered nations and from slaughtered Jews (including dental fillings, jewelry and such). It also secretly facilitated exchanges between the Nazis and supposedly neutral nations like Sweden, which sold wartime Germany most of the iron ore for its steel in exchange for looted gold. Dag Hammarskjöld, who would come to New York after the war to be secretary general of the United Nations, was directly involved as chairman of Sweden’s central bank.

The American banks not only continued to participate in BIS activities as this was going on; the director of the BIS throughout the war was in fact a Wall Streeter, Thomas McKittrick. He traveled freely in Nazi territory and Mussolini’s Italy during the war; in 1943, U-boats received orders not to meddle with the ship that carried him back to New York for high-level meetings to discuss BIS business, after which he traveled to Berlin for a debriefing at the Reichsbank.

McKittrick came back to New York when the war ended and was made vice president at the Rockefellers’ Chase National Bank. That’s not surprising. During the 1930s and the war, the Rockefeller empire, through various of its entities, maintained extensive business relations with Nazi Germany. In 1939, for example, six months before Hitler invaded Poland, Chase sent him $25 million for his war machine. The funds came from the bank’s sale of Rückswanderer (Returnee) Marks to Germans in America. RMs were another of Hjalmar Schacht’s ideas, conceived as a way to flow much-needed U.S. currency to Germany. In theory, Germans who were living abroad but intended to return to the Fatherland would buy RMs. The RMs’ value was to be credited to their personal accounts in German banks and available when they moved back. In practice, some German nationals and even Americans, never intending to move to Germany, bought RMs as a patriotic gesture of support for Der Führer – Nazi war bonds, in effect. Chase was a major broker, earning a percentage on every dollar it sent to the Nazis. The German consulate in New York, naturally, did its banking with Chase.

Chase’s collaborations with Nazi Germany look rather insignificant compared to those of the Rockefellers’ largest business, the literal wellspring of their vast family wealth, Standard Oil.

The gigantic Standard Oil monopoly that John D. Rockefeller had built in the late 1800s was broken up in the trust-busting 1910s into regional constituents, huge in their own right: Standard Oil of New Jersey, which became Exxon; Standard Oil of New York, which became Mobil, and so on. In the years leading up to the war, Standard Oil of New Jersey was the largest petroleum company in the world, with roughly four fifths of the U.S. market. Despite its name, its headquarters were in Manhattan, first in the monolithic Standard Oil Building at 26 Broadway, then at 30 Rockefeller Plaza. It did its banking, of course, with the Rockefellers’ Chase.

The two largest shareholders in Standard Oil of New Jersey were the Rockefellers themselves and the colossal German chemical cartel I. G. Farben. Farben started out at the turn of the century as a group of companies that produced most of the world’s synthetic dyes (farben is German for dye). Germany’s great weakness as a world power was its lack of the domestic raw materials needed by a modern industrial society – petroleum, rubber, iron for making steel, and other resources. The chemists at Farben solved this to a degree by developing synthetic oil and gasoline, a synthetic rubber called buna, plastics, and synthetic fibers like nylon and rayon. In other areas of applied chemistry, Farben also developed Bayer aspirin and other pharmaceuticals, Agfa film, explosives, armaments, and poison gases, including the Zyklon B that would be used in Nazi gas chambers. Several Farben chemists won Nobels.

Farben metastasized through the 1920s into the largest corporate entity in Europe, and spread around the world. It established its first outpost in the U.S. in 1929, opening the offices of I. G. Chemical Corporation at 230 Park Avenue (then the New York Central Building, now the Helmsley Building). Soon its board of directors included Edsel Ford; Standard Oil president Walter Teagle; and Charles Mitchell, president of the Morgan-affiliated National City Bank of New York (now Citibank). As it expanded in the U.S., Farben would also forge alliances with DuPont, Dow, Alcoa, and other American corporations.

By the time Hitler came to power, Farben was a phantasmagorically complex and secretive global hydra of a few thousand partnerships and cartel agreements, interlocking boards, and hundreds of subsidiary and shell corporations, a conspiracy theorist’s dream. (It plays a role in Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow.) Besides its factories and research labs, it ran its own power plants, mines, banks, patent offices, and a huge private intelligence-gathering operation that rivaled any nation’s.

All this was put at Hitler’s service in 1933. Farben was the industrial foundation on which Hitler built his war machine. Its president sat in the Reichstag; its production plants, scientists, technicians and intelligence operatives prepped and equipped the Wehrmacht for conquest. During the war, hundreds of thousands of people from occupied countries were given over to Farben as slave labor. Farben used Auschwitz captives – and worked some 25,000 of them to death – to build one of its synthetic fuel and rubber plants next-door to the death camp, where its Zyklon B was used to massacre millions more.

There was one substance Farben could not produce or synthesize in the 1930s: high-octane leaded aviation fuel. Without it, Göring’s Luftwaffe would be grounded. Only three corporations produced it. Luckily for Herr Göring, all three had close relations with Farben – Standard Oil, DuPont, and General Motors. Especially Standard, where Walter Teagle, president of the company from 1917 to 1937, then chairman of the board to 1942, as well as a director of Farben’s American subsidiary, was good friends with Farben CEO Hermann Schmitz. Teagle was very conservative, very anti-Communist, and a great supporter of Germany’s recovery in the 1920s and 1930s. He entertained Schmitz at the Cloud Room of the Chrysler Building when the German visited New York, and on some of Teagle’s frequent trips to Germany the two of them went shooting game fowl with Göring. With Teagle and Schmitz at the helms, Standard invested heavily in Farben and Farben in Standard.

In 1938, Teagle helped Schmitz get supplies of aviation fuel from a British subsidiary of Standard. The Luftwaffe planes that bombed London in 1940 were flying on this fuel. When the British government complained about American companies selling supplies to the people who were murdering them, Standard switched all its tankers to Panamanian registry. They sailed to the island of Teneriffe, where their fuel was offloaded into waiting German tankers. The planes that bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941 also flew on fuel sold to Japan by Standard Oil.

Standard and Farben also colluded on synthetic rubber. As Japan expanded its empire in the 1930s, it came to control virtually the entire world supply of natural rubber. Gas rationing and hoarding only covered part of the shortfall. Synthetic rubber was the real answer. Farben had exclusive world rights to its form of synthetic rubber, buna, while Standard was developing its own version, butyl. In a series of cartel arrangements, Standard agreed to help Farben produce butyl, and Farben granted Standard exclusive U.S. rights to produce buna – but only if and when Farben allowed it to. In short, Standard Oil agreed to help the Wehrmacht get all the synthetic tires it needed for its planes, trucks and other vehicles, while withholding the same from the U.S. military.

Roosevelt was kept informed about all this, but he was in a ticklish spot. He needed the mighty Rockefellers and Standard Oil and the Wall Street bankers for his own war efforts. Standard supplied most of the fuel used by the American military. Roosevelt had appointed Teagle to chair his National War Labor Board, and Teagle’s right-hand man William Farish to the War Petroleum Board. Within a week of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt signed an executive order amending the 1917 Trading With the Enemy Act so that he could allow certain transactions to continue.

If the Nightingale Could Sing Like You

Musicals enjoy a sort of exalted, exceptional status, depending as they do on an approach to drama that has little in common with the Robert McKee-certified story structure form.

I’m not here to kick Eyebrow Man McKee, many of whose “rules” are reasonably commonsensical analyses of how Hollywood dramas in fact work, with every scene contributing to the development of the narrative and the exploration of character. But it’s perhaps significant that the McKee model came to prominence in a time when the movie musical was moribund. Because nothing about musicals really fits in McKee’s thinking, and it’s pretty hard to make them connect smoothly to basic Platonic conceptions of drama.

Slightly Icky and Necrophiliac But All in the Service of Cinema

Lemon Pledge and death were the dominant smells: I bought a collection of ten thousand VHS tapes stored in the apartment of some recently deceased heir. Just before dying there, he'd spent his fortune on rare films, many smuggled out of archives in the pan-and-scan VHS format. My friends and I call it "The Dead Man's Sale". The occupant was apparently decomposing for days before his body was discovered. There were ground up cockroach parts in the plastic gears of the tapes. (I feel like he left his fortune, and his vermin, to me.) Anyhow, the original sources were often mysterious, shady bootleg characters whose serial killer penmanship I recognized from tapes Kim's Video used to buy. In the vast collection, I found a COMPLETE copy of GHOST TRAIN! Plus tons of Nazi-era musical comedies that made Fred Astaire look klutzy. Andre Breton now seems a piker of Surrealism to me. Some of the directors were killed by Hitler.

by Daniel Riccuito

Illustration: Tony Millionaire

Cruelty of Language: Leaked NY Times Memo Reveals Moral Depravity of US Media

The New York Times coverage of the Israeli carnage in Gaza, like that of other mainstream US media, is a disgrace to journalism.

This assertion should not surprise anyone. US media is driven neither by facts nor morality, but by agendas, calculating and power-hungry. The humanity of 120 thousand dead and wounded Palestinians because of the Israeli genocide in Gaza is simply not part of that agenda.

In a report - based on a leaked memo from the New York Times - the Intercept found out that the so-called US newspaper of record has been feeding its journalists with frequently updated 'guidelines' on what words to use, or not use, when describing the horrific Israeli mass slaughter in the Gaza Strip, starting on October 7.

In fact, most of the words used in the paragraph above would not be fit to print in the NYT, according to its ‘guidelines’.

There are Fairies in the Bottom of Our Anger

“We find that whole communities suddenly fix their minds upon one object, and go mad in its pursuit; that millions of people become simultaneously impressed with one delusion, and run after it, till their attention is caught by some new folly more captivating than the first.”

— Charles Mackay, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1841)

I’ve been reading a collection called Welsh Folk-Lore, assembled by the Rev. Elias Owen (1887, revisions 1896). I was especially intrigued by an autobiographical entry from the Rev. Dr. Edward Williams, a recollection from his youth in 1757. He and his companions, playing in a field, witnessed a troupe of swarthy, somehow inhuman, dwarf-like dancers, dressed in near-military red, one of whom chased and caught Williams, who managed to wriggle free. All raced home, then returned to the field with their families, but nothing was found of the possibly fairy dancers.

What’s captivating (and somewhat unnerving) about his tale is that it is rife with specific detail, that the man sounds in no way credulous, and that he makes no definite claims, outlandish or otherwise, as to who these figures might be; indeed he seems still mystified by them decades later as he puts down his recollections. Yet, as described, they fit well with other Celtic tales where the observer (almost always at at least one remove from the narrator) identities the entities as most definitely fairies.

What elements most likely influenced what he saw and how he interpreted his vision?

First of all, he was seven years old at the time of the meeting, so his memories had years in which to become clouded or otherwise amended.

May I Cut in Here?

A Dance to the Music of Time is one of the monuments of 20th-century British literature.

As a monument, it is immediate, cleanly chiseled, foursquare and, despite occasional intricate carvings of angels, stark. As a monument, it does not clearly disclose its sculptor – whether, in this case, it be the author, Anthony Powell, or its universal narrator, Nick Jenkins. And as a monument, at least for me, it is also less “to read” than “to have read.”

Pop Modernist Dystopia

In an interview with Peter Bogdanovich shortly before his death in 1976, Fritz Lang said of Metropolis, “You cannot make a social-conscious picture in which you say that the intermediary between the hand and the brain is the heart. I mean, that’s a fairy tale – definitely. But I was very interested in machines. Anyway, I didn’t like the picture – thought it was silly and stupid – then, when I saw the astronauts: what else are they but part of a machine? It’s very hard to talk about pictures—should I say now that I like Metropolis because something I have seen in my imagination comes true, when I detested it after it was finished?”

Lang wasn’t alone back in 1927 when the film was first released. Critics applauded the striking visuals and the ambitious technical achievement, but lambasted the trite melodrama and cheap platitudes. In a vicious New York Times review, H.G. Wells attacked the picture’s anti-progress, anti-technology message, accused it of ripping off several earlier works (including his own), and called it “quite the silliest film.” It was also attacked as a bunch of simpleminded and heavy-handed pro-communist propaganda, while at the same time and ironically enough it was hailed by the Nazis for portraying the overthrow of the Bourgeoisie.

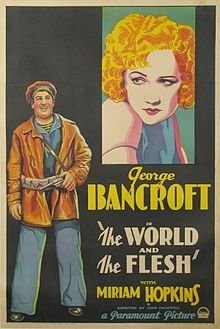

The World and the Flesh

The World and the Flesh (1932) is an obscure Paramount pre-code: there are dozens of these movies, never granted a home video release or even a TCM screening. This one is sufficiently underseen for the IMDb to have its title wrong, omitting the essential first definite article.

Evidently made under the influence of Sternberg’s slices of erotic exoticism (the same year’s Shanghai Express is particularly close), TWATF stars Miriam Hopkins in place of Marlene Dietrich, co-starring her with George Bancroft, the hulking lug Sternberg made into an unlikely star in the silent gangster flick Underworld. And it all takes place during the last days of the Russian Revolution.

Lupita Tovar: The Sweetheart of Mexico

Lupita Tovar had a short acting career during a long life, one that lasted 106 years. Passing away on the 12th of November 2016, Tovar was one of the surviving links to Old Hollywood. Between 1929 and 1952, she appeared in many supporting and bit parts. Yet Tovar was best known for her role in the Spanish-language version of Dracula (1931) and Santa (1932), one of the first talkies in the burgeoning Mexican cinema. At 5’1”, Tovar was short and sensual. Underneath pencil-thin eyebrows, her eyes were as dark as her wavy black hair, which flowed forth from her head in tight ringlets. In these two films she exudes a refined elegance and a confident sexuality, a shy naivety and a self-possessed worldliness.

Since its re-release in the 1990s, George Melford’s Dracula has grown in stature. It’s better than Tod Browning’s better-known version, although no one can rival Bela Lugosi, let alone Carlos Villarías, for iconography. Nevertheless, Melford’s film is less creaky, has more camera movement, and has the stench of eroticism missing from its English-language counterpart. As Eva Seward, Tovar is initially prim and proper. Hair bobbed, bedazzling with long, dangling earrings, and decked in white, we first see her in the box seats of a ritzy theatre, surrounded by her father, Dr. Seward (José Soriano Viosca), her friend, Lucía (Carmen Guerrero), and her boyfriend Juan Harker (Barry Norton). Fresh from Transylvania, Dracula greets them, mesmerizing Lucía and creeping out Eva. “I prefer someone a little more normal,” she says to Lucía, playfully chiding her fascination with the Count.

Shadow of the Vampire

In a medium like cinema, or, even more so, like silent cinema, that which the camera doesn’t see doesn’t exist. Or so one would think. Under the right circumstances, the unseen assumes more terrible power than anything within the frame.