The Briefly and Occasionally Great Del Tenney

He wasn’t as culturally attuned as Roger Corman. He wasn’t as obsessively prolific as Jess Franco. He wasn’t as personally flamboyant as Ed Wood. Still, writer/producer/director Del Tenney is a legend in the annals of low budget horror. That he’s a legend is in itself legendary, given that he’s remembered for only four films, all of which were made during a two year stretch in the early 1960s. I’m hard-pressed to think of another director with a filmography that brief who earned a legacy like Tenney’s. They weren’t great films, some weren’t even particularly good, but they had a spark to them, and they were undeniably memorable, sometimes for reasons that had nothing to do with the films themselves.

“My friends used to come up to me and ask, ‘How could you do all those terrible films?’’’ Tenney was fond of saying. “And I tell them, ‘I cry all the way to the bank,’”

He was born in Mason City, Iowa, but in the early ‘40s his family moved to Los Angeles. Tenney began studying theater in school, and by age 15 he was already working, both on stage and later as an extra in the likes of The Wild One and Stalag 17. His focus was on theater, though, so in the late ‘50s he moved to New York and found work in summer stock. A number of the young actors he worked with then, like Roy Scheider, Dick Van Patten, and Sylvia Miles, would later appear in Tenney’s films, many making their screen debuts with him.

By the early ‘60s Tenney and his wife, actress Margot Hartman Tenney, had also started directing productions of their own. After a conversation with a friend who was involved in (as it was described in polite company) “the exploitation film business,” Tenney took a job as assistant director on a couple of pictures, including the merely sleazy Satan in High Heels (a nasty little cheapie involving carnival strippers, junkies, robbery, sex, and murder) and nudie cuties like Orgy at Lil’s Place, (which concerned two girls who decide to get into the nude modeling racket). In later years, while Tenney spoke freely about the former, he rarely mentioned the latter. Still, his experience there inspired him to start making films of his own.

While in the theater he preferred to stick with Shakespeare and the classics, when he moved into film it was all about the bottom line. His goal was not to make great art, but to make a few quick bucks, and to do that he knew what audience he had to aim for. He was determined to give them exactly what they wanted.

Seeing potential in a story his wife had told him about a girl she knew in college who was found murdered, in 1962 Tenney sat down and began working on a script he initially called Black Autumn. Later it would be called Violent Midnight. Then shortly before its release the distributor changed the title to Psychomania, thinking it would cash in on Psycho and pull in the kids.

Financed by his father-in-law and filmed (as all his pictures would be) in Stamford, CT, Psychomania focused on a string of brutal sex murders in a small college town. The obvious suspect is that eccentric painter with a family history of mental problems who lives all alone out in the boonies and paints nude models who often end up getting stabbed (Lee Philips). The above-mentioned Dick Van Patten and James Farentino co-star as a couple of suspicious detectives, and Sylvia Miles appears, well, doing that great Sylvia Miles thing.

It’s a sharp and surprisingly stylish little b/w suspense thriller clearly influenced not only by Hitchcock in the camera work, but also by film noir and horror films of the ‘30s and ‘40s in its use of deep shadows. The shadowy murder scenes are especially shocking here. But none of that really mattered. The picture guaranteed its drive-in popularity by including plenty of nudity along the way. In fact prior to its release the same distributor who changed the title also insisted on more boobs, so without any tantrums about “integrity” or “artistic vision,”Tenney went back and shot another ten minutes of skin and mild sex and cut it in.

Although Richard Hilliard receives the on screen credit as director and Tenney’s only credit is as producer, he would later say that Hilliard was a friend of his and a theater person who knew nothing about making films or dealing with actors, so he had to step in himself and take over, making this the first picture he wrote, produced, and directed.

The film made a lot of money (given its budget, anyway) but today is the least recognized of his films. That always confused me a little, given that in technical terms alone it’s the best thing he ever did. But I guess that’s not what people are always looking for in low-budget films.

There’s something else going on in Psychomania, though, that I’ve been touting for years even if no one seems to care. In terms of genre film history, those self-satisfied types who concern themselves with such things comfortably and endlessly cite Mario Bava’s Blood and Black Lace as the first giallo, the film that launched a thousand copycats made by everyone from Fulci to Argento. The Bava film is the immovable cornerstone. Without taking anything at all away from what is undeniably a great picture, I’d still argue that Tenney beat him to the punch. Psychomania (released on DVD as Violent Midnight) contains everything that would later be cited as fundamental to any giallo picture: a string of sex crimes, an obvious suspect, several other obvious suspects, lots of boobs, savage violence, and a twist ending. But Psychomania was released in early ‘64, roughly 14 months before Bava’s picture. Okay, so maybe it’s not Italian, and maybe it wasn’t based on those tawdry little yellow paperbacks that were so popular at the time, but dammit it’s still a giallo, and it was the first.

I’ll shut up about that now.

After making a film with style, intelligence, and even a little class compared to the usual drive-in fodder, a film whose influence would be felt for the next twenty years (even if no one will admit it), and a film that made him a little money, Tenney took a hard left.

Filmed over two weeks in 1962, Curse of the Living Corpse was a costume melodrama set in 1892 that’s reminiscent of those AIP prestige numbers or early Hammer films. When a wealthy, possibly crazy, and just plain mean old man dies, his will stipulates that if the surviving members of his family don’t shape up and fly right, he’s going to rise from the grave and kill them off one by one. Well, they don’t and he does. Or at least it looks like that’s what’s happening.

It’s still a film with style, intelligence, and class, but of a different kind. While Psychomania was intense, sexy, and at times brutal, Curse of the Living Corpse was a very stagebound, theatrical piece, a bit slower, a bit more deliberate. A sitting room murder mystery heavy on the dialogue, punctuated here and there by a thematic murder. Plus most of the characters are wearing too many layers for things to get terribly sexy.

Curse features Roy Scheider (in his film debut) as one of the profligate heirs in question, Carnival of Souls’ Candace Hilligoss, and Tenny’s wife Margot Hartman. It’s one of the things that has always made Tenney’s films, cheap, fast, and DIY as they were, stand out. By pulling in friends from the theater, good, professional actors willing to work on a goofy movie for no money, he ended up with performances several cuts above what you’d normally find in something like this. When none of the actors in a costume drama are, say, chewing gum, it just adds a layer of credibility to the story, no matter how ridiculous that story might be.

The other thing that made Tenney’s first two films stand out was the sharp b/w cinematography. The shadows are so deep here, the contrast so sharp and detailed, the film at times reminds me of those early Bava pictures (to go back there again). Even when the story lags a bit, the atmosphere carries it along. It’s something that can’t often be said about the low-budget pictures of the era.

Well, even as he was still working on Curse of the Living Corpse, pre-production was underway on his next film, The Horror of Party Beach. Shooting began about three days after Curse wrapped. If Tenney took a hard left from Psychomania into Curse, this time he had to jump all the way to the other end of the spectrum.

He admitted he wasn’t sure the genre-mashing satire, the horror musical beach movie, would work, but he charged ahead anyway. What made it work was sticking so tightly to the conventions of both the bug-eyed monster film and the beach blanket movie, while at the same time pointing up the ridiculousness of those conventions. Plus there’s a great fucking soundtrack provided by the Jersey-based surf band The Del-Aires.

In the film’s first five minutes he lays everything out. We meet an assortment of young attractive couples and character types on the beach, each with issues of their own. We meet the potential (human) villains in the form of a local motorcycle gang. And out in Long Island Sound, nuclear waste is being dumped into the water where it settles down on a shipwreck and transforms (with the aid of some neat in-camera trickery) the skeletal remains of lost sailors into an army of fishmen in search of human blood.

After that, well, there you go. The monsters are intentionally silly takeoffs on the usual “man in a rubber suit” creatures (note particularly the eyes and the teeth). But if the monsters are silly, so are the people, and in between the two Tenney crams in as many drive-in standbys as he can fit: motorcycle chases, baffled scientists, malt shops, some of those crazy teenage dances, doomed drunks, convertibles, incredulous cops, superstitious black maids who accidentally save the world. And he holds it all together with some editing that’s a bit more clever than you’d expect. The first victim, for instance, dies during a series of cuts between the attacking fishman and The Del-Aires performing the unbelievably catchy “Do the Zombie Stomp” to a bunch of dancing teenagers on the beach. For something this goofy it’s surprisingly disturbing.

(Jokes and surf bands aside, Humanoids From the Deep owes a serious debt of gratitude to Horror of Party Beach).

This and Curse of the Living Corpse were released as a double bill by 20th Century Fox later in ‘64, complete with a gimmick. Would-be audience members were required to sign a release before entering the theater absolving the theater owners of any blame should the viewer die of fright during the screening. It’s unclear if there were any casualties.

The double bill was the last thing to play at the legendary 3,000-seat Paramount Theater in Times Square, and Horror of Party Beach went on to become Tenney’s most successful film. After that things started to slip.

His next picture, which he completed in ‘64, was Voodoo Bloodbath, a horror comedy that can trace its roots directly back to Val Lewton’s classic I Walk With a Zombie, but with more bad jokes. William Joyce stars as a bestselling, wisecracking, playboy author of adventure novels. Given that he hasn’t turned anything in to his editor for months, his editor drags him onto a plane and flies him to, yes, Voodoo Island in search of inspiration. See, not only is a famed scientist conducting cancer research there, but the place is supposedly overrun with zombies, too.. It’s a million-selling novel in the waiting. When they arrive they discover three things:

1. The Caribbean island is actually populated by Mexicans for some reason.

2. The scientist has a beautiful blonde virgin daughter.

3. The local natives are preparing for a human sacrifice that night.

None of it bodes well for anyone, though no one realizes this yet.

The humor arises mostly from the editor’s shrill and boorish wife, and the author’s overbearing attempts to pick up any woman he sees (particularly the scientist’s daughter). Neither are terribly funny. The rest of the film is straight-faced and boilerplate, reminiscent of a dozen voodoo pictures from the ‘40s. It’s not very good, either. Compared with his first two films in particular the production values and direction had gone straight to hell. It’s a clumsy, sloppy picture with very little charm. There’s not even much of a bloodbath. Drumming’s good, though. Up to this point he had worked near miracles with standard storylines and no budgets by bringing in good actors and skilled editors and cameramen. Here he didn’t seem to be trying all that hard. Of all four films, this one really did look and feel like everything else out there.

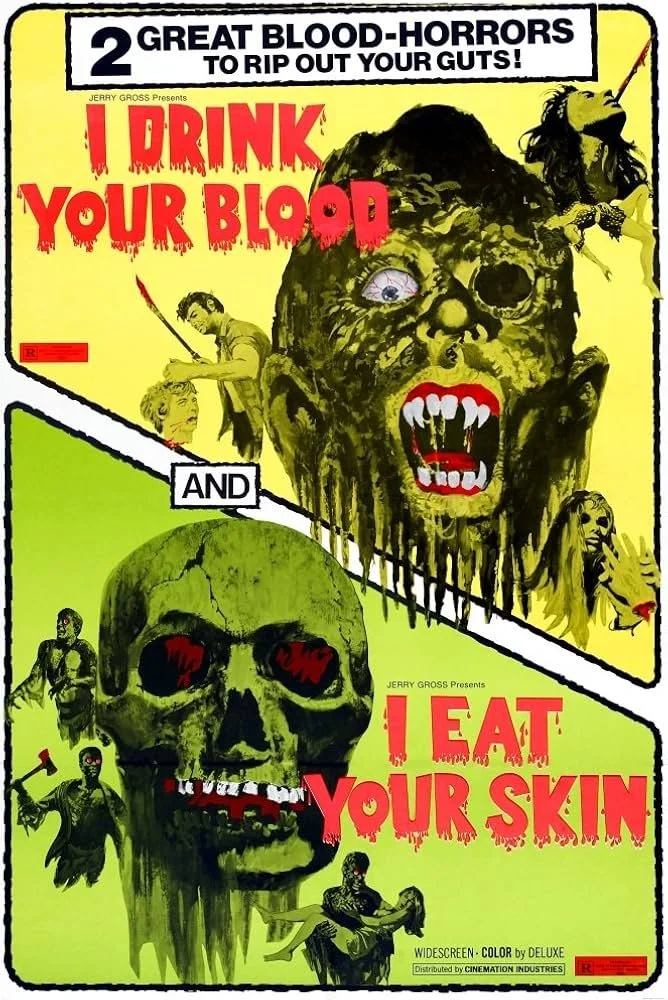

I wasn’t the only one who thought it could’ve been better. The picture sat on the shelf for nearly seven years until 1971, when low-budget distributor Jerry Gross came nosing around in search of a film to drop in the bottom half of a double bill he had in mind. After a quick and simple title change, the Tenney film was just the ticket he was looking for. As great and fun as those first three films had been, it was Gross who, if accidentally, helped make Tenney a legend.

Today Voodoo Bloodbath is all but completely forgotten. Even under its new title, I Eat Your Skin is less remembered for what it is as a movie than for being half (together with the utterly unrelated I Drink Your Blood) of one of the most notorious double bills ever released. After seeing them we may not remember anything that happened in either, but we sure do remember those newspaper ads, and sometimes that’s worth a hell of a lot more.

Tenney didn’t talk much about the experience or the film after the fact, but while Voodoo Bloodbath was still sitting on the shelf he all but completely stepped away from the film business, though he admits he kept the monster suit from Horror of Party Beach and wore it at parties. He and his wife had never strayed from Connecticut, never became part of the hobnobbing Hollywood crowd, so they simply settled down where they were all along, and returned to their first love. They founded what would become a very well respected theater company, putting on three or four productions a year.. Years later when they moved to Florida they opened another. In between Tenney got involved in real estate up and down the East Coast.

Then in the late ‘90s, over thirty years after retiring from motion pictures, he and his wife, together with producer/director Kermit Christman (Wicked Games) , founded DelMar Productions and Tenney began writing, producing and directing again. Between ‘99 and 2003, he made three pictures: Clean and Narrow, about an ex-con trying to go straight in a small town; an I Know What You Did Last Summer knockoff called Wanna Know a Secret?; and a supernatural thriller called Descendant, in which a would be writer is haunted by the spirit of an ancestor who happens to be Edgar Allan Poe. The last was particularly dear to Tenney, because he’d always loved Poe and wanted to do some kind of movie about him.

Ah, but the movie business was a very different animal by then. It wasn’t merely a matter of borrowing a few bucks from your father-in-law to make a silly monster picture, then hooking up with an independent distributor. Now even making the smallest film meant raising a few million dollars. Worse, the lawyers had gotten involved. And forget about any kind of distribution if you aren’t connected to a major studio. The fun had been sucked out of the game, and this was evident in the films themselves. Sure those films he made in the ‘60s were blatantly, even cynically commercial, but commercial in a ragtag, adventurous, slapdash way. The new films were commercial, but much more carefully so. They were slick and serious. If they weren’t slick, audiences wouldn’t look at them, and you had to be serious about the whole process, because there were millions of dollars at stake. Hell, there was even a desperation evident on the screen. While before Tenney had been working with a bunch of young actors on their way up, now he was working with a bunch on their way down (William Katt, Sondra Locke, Wings Hauser), and you can almost hear their nails scratching as they scramble to hold onto anything at all before they vanish completely.

No, it wasn’t much fun, But those aren’t the films Tenney will be remembered for, and they won’t take anything away from his status among fans. He’ll be remembered for those four pictures from back in ‘64 (even if one wasn’t released until ‘71). They weren’t as good as some, but a lot better than most. In all four pictures he never once repeated himself. They were all radically different in mood and style and story, and there was a seductive, sloppy magic about them that’s inescapable. No matter how many times I go back to Psychomania/Violent Midnight (and I go back to it a lot) the ending still catches me off guard. After all these years “The Zombie Stomp” still gets stuck in my head. I even find myself returning to I Eat Your Skin every couple years, not to laugh at it, but just to wonder. I guess that’s why Tenney, on the basis of only those four pictures, can now take his rightful spot among the pantheon of cult directors.

by Jim Knipfel