The Aristocrats of Film Noir

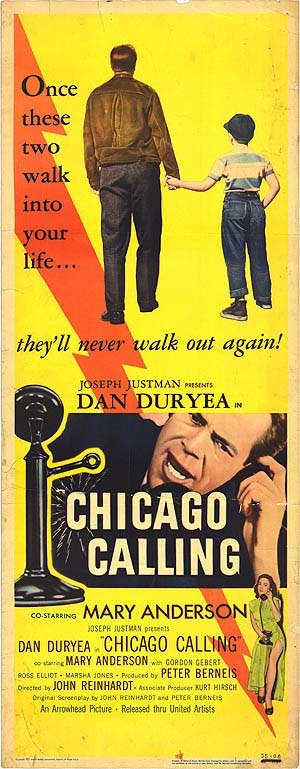

Film Noir was never fundamentally a genre of shadows, but rather defined itself as a set of underlying attitudes and assumptions — All Talking Pictures were poised, Johnny-on-the-spot, to save the country; or to capture the ensuing madness when the stock market crashed in 1929. Instead of catching the fall of executives throwing themselves out of windows, Noir caught the fall of the masses down below. It’s tempting to posit Black Tuesday as the date of Noir’s metaphysical birth, and to suggest that economic calamity and advancing technology met for preordained reasons. Let us give in to that temptation.

After all, what other apostate canon could possibly have contrived a cinema where raw anger is so central; where, rendered visually, it is the prescription to discard standard canonical shorthand like “genre” or “classic” — spawning instead this previously unknown brood of redheaded stepchildren twisting in the womb of American moviedom? The films themselves cry out for a cinematic death. Pursued through abandoned industrial parks and labyrinthine sewer systems, Noir characters are born tickets punched, fate sealed. The black-listed, and therefore uncredited, Lionel Stander narrates 1961’s Blast of Silence, pronouncing “hate” more times than anyone has counted. Listen for the unmistakable echoes of Stander’s corroded instrument as this, the most prosperous nation of late modernity comes tumbling around us.

Long before the official beginnings of Noir in the Forties, Hollywood thrillers routinely used the visual tropes of dark shadows, low-key lighting, expressionist angles, and featured detectives, gangsters etc. What Noir added was a sense of corruption, of capitalist society gone awry (or, perhaps, working exactly as it was supposed to, to the detriment of honest citizens). Post-WWII, this served as a release of pent-up pressure: criticism of the status quo had been seen as unpatriotic during the war. Suddenly, it was acceptable, even desirable, to turn that righteous anger inward, against domestic problems. Veterans lugged their battlefield violence home with them, an American principle brought to new fruition. Or to quote dirty cop Detective Lieutenant Barney Nolan (Edmond O’Brien) in 1954’s Shield for Murder…

The Chiseler Interviews Jonathan Rosenbaum

The Chiseler’s Daniel Riccuito discusses pre-Code talkies, noir and leftist politics with one of America’s leading film critics.

DR: We share a common enthusiasm for early talkies. Do you have any favorite actors, writers or storylines relating to the period’s ethnic, often radically left-wing, politics? I’m thinking of the way that, say, The Mayor of Hell suddenly busts into a long Yiddish monologue. Or movies like Counsellor at Law and Street Scene present hard Left ideas through characters with Jewish, Eastern European backgrounds.