The Aristocrats of Film Noir

Film Noir was never fundamentally a genre of shadows, but rather defined itself as a set of underlying attitudes and assumptions — All Talking Pictures were poised, Johnny-on-the-spot, to save the country; or to capture the ensuing madness when the stock market crashed in 1929. Instead of catching the fall of executives throwing themselves out of windows, Noir caught the fall of the masses down below. It’s tempting to posit Black Tuesday as the date of Noir’s metaphysical birth, and to suggest that economic calamity and advancing technology met for preordained reasons. Let us give in to that temptation.

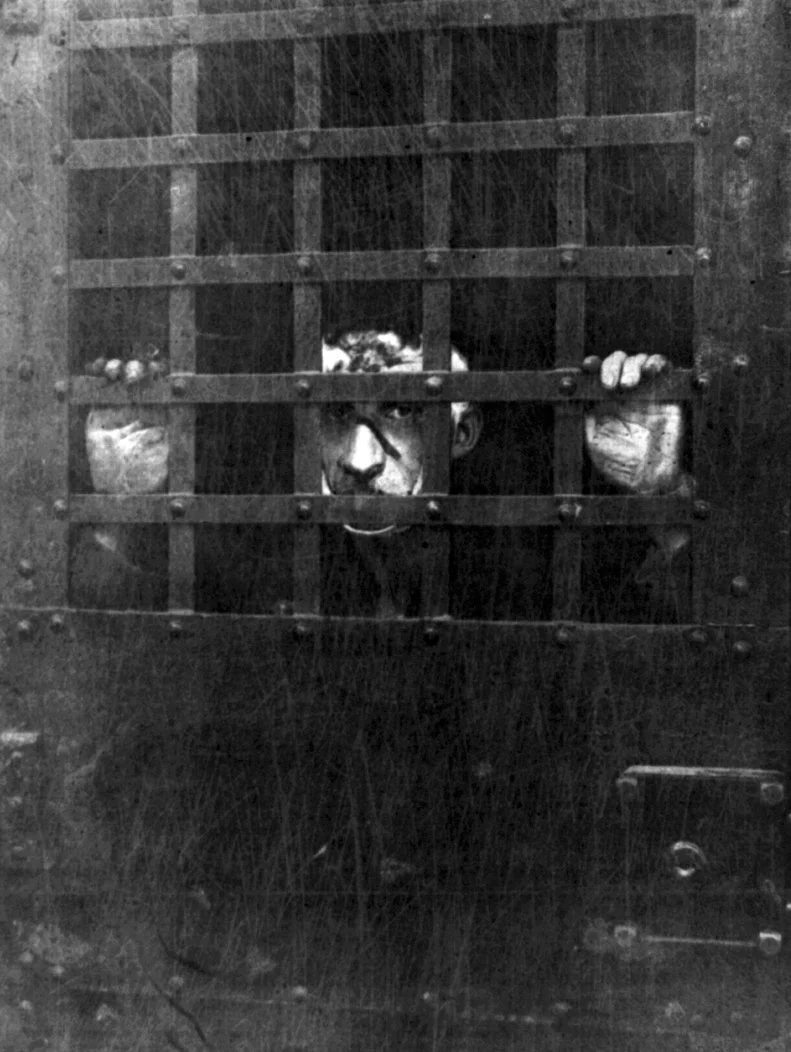

After all, what other apostate canon could possibly have contrived a cinema where raw anger is so central; where, rendered visually, it is the prescription to discard standard canonical shorthand like “genre” or “classic” — spawning instead this previously unknown brood of redheaded stepchildren twisting in the womb of American moviedom? The films themselves cry out for a cinematic death. Pursued through abandoned industrial parks and labyrinthine sewer systems, Noir characters are born tickets punched, fate sealed. The black-listed, and therefore uncredited, Lionel Stander narrates 1961’s Blast of Silence, pronouncing “hate” more times than anyone has counted. Listen for the unmistakable echoes of Stander’s corroded instrument as this, the most prosperous nation of late modernity comes tumbling around us.

Long before the official beginnings of Noir in the Forties, Hollywood thrillers routinely used the visual tropes of dark shadows, low-key lighting, expressionist angles, and featured detectives, gangsters etc. What Noir added was a sense of corruption, of capitalist society gone awry (or, perhaps, working exactly as it was supposed to, to the detriment of honest citizens). Post-WWII, this served as a release of pent-up pressure: criticism of the status quo had been seen as unpatriotic during the war. Suddenly, it was acceptable, even desirable, to turn that righteous anger inward, against domestic problems. Veterans lugged their battlefield violence home with them, an American principle brought to new fruition. Or to quote dirty cop Detective Lieutenant Barney Nolan (Edmond O’Brien) in 1954’s Shield for Murder…

All the World’s a Stage

In 1988, a socio-linguist at the university of Pennsylvania posted a note on the departmental bulletin board announcing she had moved her late husband’s personal library into an unused office. Anyone who wanted any of the books should feel free to take them. Her husband had been the chair of Penn’s sociology department. They’d married in 1981, and he died the following year at age sixty. Normally you’d expect the books and papers to be donated to some library to assist future researchers, but she’d recently remarried, so I guess she either wanted to get rid of any reminders of her previous husband, or simply needed the space.

At the time my then-wife was a grad student in Penn’s linguistics department, and told me about the announcement when she got home that afternoon.

Well, had this professor’s dead husband been any plain, boring old sociologist, I wouldn’t have thought much about it, but given her dead husband was Erving Goffman, I immediately began gathering all the boxes and bags I could find. That night around ten, when she was certain the department would be pretty empty, my then-wife and I snuck back to Penn under cover of darkness and I absconded with Erving Goffman’s personal library. Didn’t even look at titles—just grabbed up armloads of books and tossed them into boxes to carry away.

As I began sorting through them in the following days, I of course discovered the expected sociology, anthropology and psychology textbooks, anthologies and journals, as well as first editions of all of Goffman’s own books, each featuring his identifying signature (in pencil) in the upper right hand corner of the title page. But those didn’t make up the bulk of my haul.

There were Catholic marriage manuals from the Fifties, dozens of volumes (both academic and popular) about sexual deviance, a whole bunch of books about juvenile delinquency with titles like Wayward Youth and The Violent Gang, several issues of Corrections (a quarterly journal aimed at prison wardens), a lot of original crime pulps from the Forties and Fifties, avant-garde literary novels, a medical book about skin diseases, some books about religious cults (particularly Jim Jones’ Peoples Temple), a first edition of Michael Lesy’s Wisconsin Death Trip, and So many other unexpected gems. It was, as I’d hoped, an oddball collection that offered a bit of insight into Goffman’s work and thinking.

“I’ve Got Money Singing in My Brain!”: DECOY (1946)

It’s just one cruel joke after another. An executed man is brought back to life, only to be shot dead minutes later. A noble doctor who has devoted his life to serving the poor is seduced and duped by the world’s most avaricious woman, who shrewdly points out, “You like to smell the perfume I use. This perfume costs $75 a bottle.” Her partner in crime enjoys gloating over her victims, only to become one of them when she stomps on the gas pedal while he changes a flat tire. As she lies dying, the woman asks the cop who has hounded but reluctantly admires her to “come down to my level, just once”; then as he finally succumbs and leans in for a kiss, she laughs in his face. For a finale, the box of loot she died for turns out to be filled with worthless scrap-paper. It’s the decoy; so is she; and so is money, the love-substitute, sex-substitute, life-substitute that makes this grubby world go round.

Cliff Edwards: He Did It With His Little Ukulele

Cliff Edwards is better known as Ukulele Ike, and best known as Jiminy Cricket. But cast an eye down his movie credits, from 1929 through 1965, and the names of his characters form a jazzy found poem of monikers. He was Froggy, Foggy, Owly, Pooch, Snipe, Bumpy, Screwy, Louie, Stew, Dude, Rooney, Snoopy, Pinky, Sleepy, Shorty, Runty, Speed, Tip, Tips, Hogie, Handy, Happy, Harmony, Nescopeck, Minstrel Joe, Banjo Page, Bones Malloy, and—my personal favorite—Squid Watkins. This slang menagerie says a lot about the off-beat appeal of one of the 20th century’s most unique and endearingly oddball talents.

Clifton A. Edwards was born in 1895 in Hannibal, Missouri, hometown of that other great American master of the nom de plume, Mark Twain. He grew up poor, selling newspapers on the street. A natural performer, he ran away and by 16 was singing in saloons and carnivals in St. Louis, where he picked up his nom de uke courtesy of a waiter who couldn’t remember his real name and dubbed him Ukulele Ike. He had adopted the tiny Hawaiian guitar and the kazoo so that he could accompany himself as an itinerant entertainer. He rose through vaudeville, teaming up with the comedian and eccentric dancer Joe Frisco, then achieved his first great success on Broadway in the 1924 Gershwin show Lady Be Good, starring Fred and Adele Astaire, in which Edwards introduced the hit “Fascinatin’ Rhythm.”

His trademark instrument, with its comical size and association with 1920s hot-cha frivolity, suited Edwards’ vaudevillian persona, but may have tended to obscure his serious gifts as a musician. He does get credit for being among the very first white artists who can truly be called a jazz singer; he knew how to swing a song and how to elaborate on it by scatting and imitating instruments—in his case, with wild kazoo-like choruses, bluesy muted-trumpet growls, and uninhibited yowls suggestive of a cat on a back fence. But Edwards could also croon a straightforward love song in a high yet natural tenor—pure, warm and unadorned—that is far from the ludicrously effeminate falsetto affected by many twenties crooners, or the limp, wan stylings of Rudy Vallee. He could even redeem sentimental pablum with his simple and tender delivery. Though he lacked suave looks or a husky, sexy voice like Bing Crosby’s, he brought vulnerability and honesty to love songs without ever slipping into the maudlin.

Méliès and “The Divisible Man”

Georges Méliès reimagined physics. And, in the process, put to shame Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. Renaissance empiricism was, momentarily, kaput. If one had a mind to catalogue Méliès’ ingenious transformations, then a plausible title might be “The Divisible Man”: detachable head, multiplying detachable head, expanding detachable head, the head as heavenly body, the body smithereened and reassembled… But of course a modern, tech-based art form like cinema makes “originality” itself suspect. Méliès cannibalized the works of Verne, H.G. Wells and Poe, or poached from their hunting grounds, without worrying in the least about copyright, and documented the same sorts of fantastic voyages to the moon, the south pole and the ocean floor, by outsize, inhabited artillery shell, by balloon or airship, rocket-train, or whatever fantastical machine could be cobbled together in his greenhouse studio. While the literary fantasists were somewhat concerned with credibility, with the science part of science fiction, the Frenchman with the upside-down head (bald top, hairy underside) focussed purely on visual possibilities: an idea was only any good if it gave you an IMAGE.

Ophelia by the Yard

Cobwebbed passages and wax-encrusted candelabra, dungeons festooned with wrist manacles, an iron maiden in every niche, carpets of dry ice fog, dead twig forests, painted hilltop castles, secret doorways through fireplaces or behind beds (both portals of hot passion), crypts, gloomy servants, cracking thunder and flashes of lightning, inexplicably tinted light sources, candles impossibly casting their own shadows, rubber bats on wires, grand staircases, long dining tables, huge doors with prodigiously pendulous knockers to rival anything in Hollywood.

Here was the precise moment — and it was nothing if not inevitable — when the darkness of horror film, both visible and inherent, leapt from the gothic toy box now joined by a no less disconcerting array of color. The best, brightest, sweetest, and most dazzling red-blooded palette that journeyman Italian cinematographers could coax from those tired cameras. Color, both its commercial necessity as well as all it promised the eye, would hereafter re-imagine the genre’s possibilities, in Italy and, gradually, everywhere else.

Death in Venice, California

On February 1, 1963, Night Tide lapped like an expressionist wave against the screens of American drive-ins and art houses, not to mention the Times Square grind house where Truman Capote saw, and absolutely treasured, Curtis Harrington’s 1961 opus. Night Tide rolls in with the satiny force of its leading lady, Linda Lawson, whose breathy voice expresses alien intensity lurking behind an opaque curtain of melancholia.

It had spent three years languishing in the can when distributor Roger Corman smuggled the unlikely masterwork into public consciousness, another of his now legendary mitzvahs to art. Throughout Night Tide, a strangely hushed invitation lingers in the air: "Come live above a merry-go-round, have breakfast with a hot sailor and an even hotter mermaid, spend hours with an old drunk captain, listening to the strange tales behind the morbid souvenirs of his life.”

Zoetic Leaves

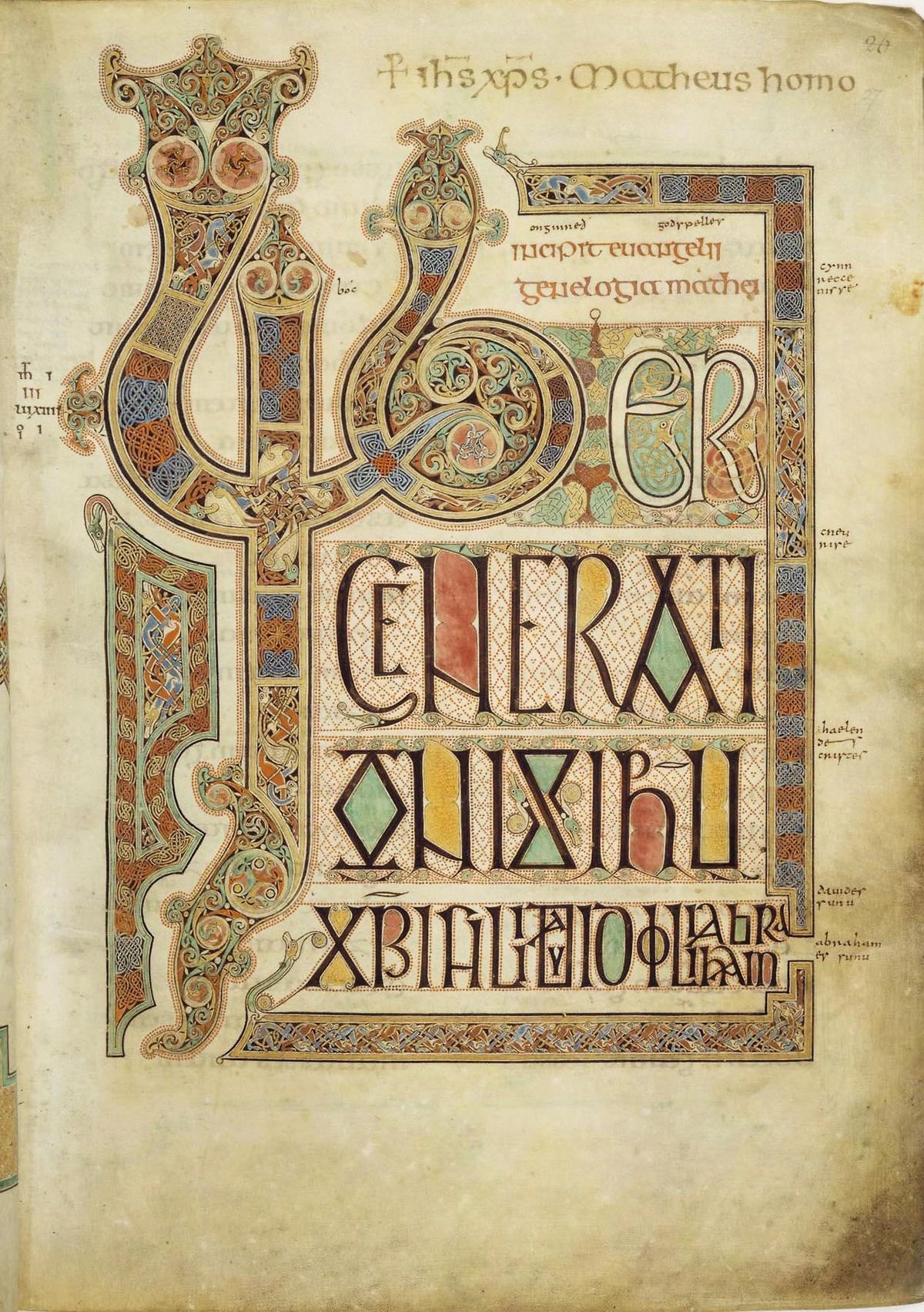

It is the custom of illuminated manuscripts to transform sacred words into shimmering icons which break, easily, beyond the sensory limitations of simple text, rendering ordinary letters into evocative, animate visual forms that invite the eye to linger at the brink of transcendence, rather than standing at a distance, remote and unyielding, daring to be comprehended, accepted, believed. Strange and barely recognizable wildlife appears on vellum leaves, creatures that wind and unwind in ceaseless whirlpools of bejeweled abstraction. Or, if you prefer, these are the animated exoskeletons of snakes, dragons and waterbirds — Celtic and Germanic obsessions meeting the Apostles of Christendom. Emerging in the British Isles between 500–900 C.E., The Lindisfarne Gospels provide an arena, lapidary and starlit, where paganism devours Christianity while also birthing the religion anew into “motion pictures”.

Put simply, movies are books made from light, zoetic leaves and letters that move beyond their trellis, leaving us to decipher a purely visual enigma; one all the more impossible to contain within mortal consciousness because the light of this steadfastly irrational art has swallowed up the text.

There are those, however few in number, who have decoded this cryptic iconography, but mysteries remain, not unlike those mysteries — strange, delved, bewildering — contained within the gospels.

They are mysteries that urge upon us a wholly radical reconsideration of silent film; of the book in film, of whispering pages; pages fluttering like leaves. Of Stan Brakhage, who gave us a series of works entitled The Book of Film and otherwise seemed incapable of regarding the universe independent of its sensual properties. Of Hollis Frampton and Peter Greenaway. Certainly of Robert Beavers, who incorporates the sound and motion of turning pages — placed in relationships and analogies with other actions — and the moving of birds wings in flight. This is not the middlebrow idea of film as purely narrative-bearing text. It is Mallarme’s concept of the book, the Proustian notion of the book. It is its ultimate realization, par excellence, and by far the most apposite. The films of David Gatten, which deeply engage with the idea of the book, the history of books. These are works that require different modalities of reading/touching words and saccadic rhythms involving different velocities of hyphenation and partial retention and compound phrases through the softest of collisions.

A Genesis Out of Light

Would it be preposterous to argue that movies are essentially projected books, books made out of light? Even weirder, let’s entertain the idea that Jules Verne’s science-fiction imagery, which finds itself transfigured early in the development of cinema, is not alone: the audience — you, me and everyone watching — dissolves into moving illustrations. “Motion pictures”. A horrifying thought if we “foolishly” believe that our three-dimensional selves could squish, flatten (and like it!).

Dating at least as far back as Georges Méliès, the cinema of bodily transformation did not necessarily equate with “horror” per se. The horror film was eventually codified as genre from the cinema of bizarre attractions exemplified by Lon Chaney, master of grotesque makeups and bodily contortions, but in the early cinema it was standard procedure to have one's detached head inflated to fill the room (The Man with the India Rubber Head) or multiplied into a row of bodiless noggins, singing or rather mouthing in harmony (The Four Troublesome Heads). Then came Nosferatu, preordained to shimmer on-screen. Vampires, immortals of the night, slain by sunlight, rose out their tombs in the movie theaters of the 1920s and never returned. They sit next to us in the dark, having ceded the power of hypnotism to the glowing screen itself. Photochemical vagaries invariably allow movie darkness to behave in uncanny ways; as if the physical properties of film followed no rules, and thus invited us to accept its essential anarchy without question. Before us, the darkness GLOWS.

Night Tide

Canonical stature is both fragile and contingent, and that’s why powerful institutions seek to shore up the various canons with rankings and plaudits. We’ll play along by asserting that one of our favorite “B” movies was originally screened by Henri Langlois at the Cinematheque française with Georges Franju in attendance. Night Tide (1961) was an unlikely contender for this particular honor—shot guerrilla-style on an estimated $50,000 budget, and intended, at least by its distributors, for a wider, less demanding audience seeking mostly air-conditioned escapism.

Mae Clarke: An Honest Woman

There is a certain look of wary, contained bitterness that you see on women’s faces in movies from the early thirties. Their eyes become veiled; the women seem to retreat inside themselves defensively, tasting memories of hurt and humiliation, of men who made them feel dirty and how they had to keep on smiling and flirting so they could pay the rent on their drab hall rooms and buy their automat coffee. It’s the look of the chorus girl who has learned to protect herself by shutting down the gates, even while wiggling in her scanties. Barbara Stanwyck carried it throughout her long career, like an eternally livid scar; “bubbly” Joan Blondell wore it quietly; and in Waterloo Bridge (1931) it’s branded on the face of Stanwyck’s one-time roommate, Mae Clarke.

Waterloo Bridge opens with a shorthand summation of a chorus girl’s life. It’s the all-hands-on-deck finale of a fluffy musical revue on the last night of its run. The camera pans past the interchangeable faces of the chorines in their platinum wigs and sparkly tricorn hats, and comes to rest on Mae Clarke, as Myra Deauville. She throws up her arms and gives an open-mouthed laugh, then lapses into exhausted boredom, then switches on the faux exuberance again, then yawns. Throughout the film she keeps doing this: putting on her game “Hello, big boy” act and then flinging it aside with furious disgust. Director James Whale doesn’t bother with transitions, but conveys the whiplashing ups and downs of his heroine’s life through blunt cuts. We see her backstage in her bra, receiving a white fox stole from an admirer; in the next scene, out of work for two years, she’s wearing the stole low around her décolletage, standing outside the theater with a fellow hooker looking for pickups. (The setting is World War I, but when Myra says hopefully, “I’ll get a job soon,” 1931 audiences must have foreseen the worst.)

Spotting a prospective john, the friend primps and smiles flirtatiously, while Myra turns on him with a defiant yet seductive scowl; a sullen, defensive stance that she assumes throughout the film. She suffers from incurable decency, which becomes a scalding torment when she meets an innocent young doughboy who has no idea that she’s a prostitute. She brings Roy (Kent Douglass) to her flat, intending to pluck him for the back rent she needs to satisfy her sour-faced landlady. But it’s too easy: when the sweet, boyish soldier pleads with her to accept the money, she abruptly drops the good-natured frankness she’s been charming him with and turns hard and caustic, hating him because she hates herself for tricking him. She’s so stung with hurt pride that she has to lash out and hurt someone else. Preparing to go out on the streets after sending him away, she stares at her hard face in the mirror, dabbing make-up on the rigid mask that barely conceals the tired, angry sadness beneath.

Waterloo Bridge is the only film that reveals the breadth of Mae Clarke’s talent. In other movies she played nice, open-faced girls or mean, petulant golddiggers. As Myra she is a kaleidoscope of confused emotions. Her best scene comes when Roy tells her he loves her: she turns away, hunched as though against a cold rain, her eyes narrow and tense. This is the final insult from life: for her dream guy to come along too late, when she feels unworthy of him. Leaving, he kisses her hand, and reacting to this tribute she passes through exaltation, anxiety, and rage—growling as she forces herself to cast it aside. She’s too honest to grab the expedient of letting a man make “an honest woman” out of her. But we know she loves him, because in the next scene she’s trying to knit him a pair of socks, sitting at the breakfast table with her hair piled on her head, a cigarette planted in her mouth, mangling the stitches.

The worst is yet to come: well-meaning oblivious Roy tricks her into visiting his posh family in the country. They’re kind and welcoming in that self-satisfied upper-class way bound to cause excruciating discomfort in someone like Myra. Roy’s mother (Enid Bennett) is polite, complacent and deadly. Watching her sweetly confide to Myra that she doesn’t want her son to marry a chorus girl, but that she knows she has nothing to fear from such a “fine” person, is almost unbearably painful. Reduced to abject guilt, Myra confesses her true profession and pitifully sobs, “I just wantcha to know, I could’ve married him…”

Great Zilches of History

Film is light. There are times, though, when that light may take on a Stygian cast, burning with a flamme noire severity, a weird and otherworldly keenness. Or it may burn lurid and loud — especially if it’s a very old film, acting like a séance that summons the unruly dead. The darkness in cinema best typified by that form we call film noir is in its essence an extension of the peculiarly American darkness of Edgar Allan Poe.