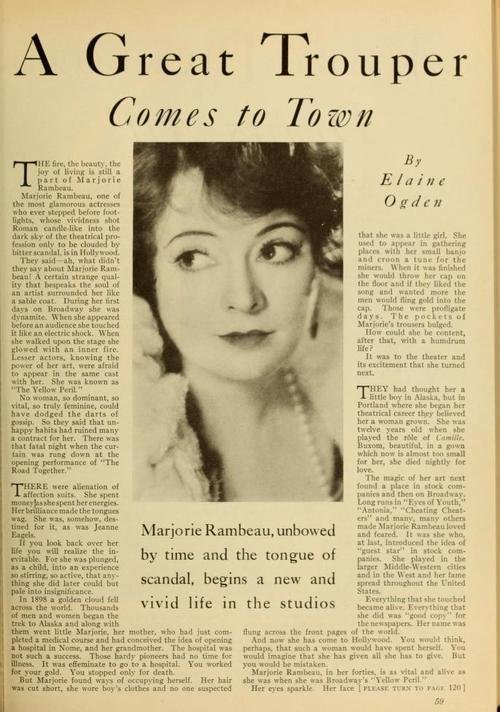

Marjorie Rambeau: The Trouper

One of J.M. Barrie’s “half hours” of diamantine dramatic compression, Rosalind, gives its lead actress the irresistible opportunity to play an actress playing an actress. Apparently sunk in the doughy delights of middle age, she takes in a rain-soaked hiker who turns out to be an admirer of the “daughter” whose photo adorns her mantlepiece, the actress Beatrice Page. She reveals that she is the daughter, on holiday from the demands of the stage that have kept her alone and eternally twenty-nine: “Blame the pitiless public that has made me what I am. I am their slave and their plaything, and when I please them they fling me nuts.” At this point a telegram from the theater summons her to rescue a flagging season by reviving her infallible Rosalind in As You Like It, and she plods off to prepare to catch the London express. Her young swain manfully pleads through the door to rescue her from her treadmill and be a support to her middle age. Sensation! Through the door swoops a slim, sparkling, refurbished Beatrice Page, champing to hit the boards again: “The stage is waiting, the audience is calling, and up goes the curtain. Oh my public, my little dears, come and foot it again in the forest, and tuck away your double chins. … They are my slaves and my playthings, and I toss them nuts.” What actress could resist?

Marjorie Rambeau is probably most familiar to us today in her Pre-Code incarnation as a yowling bag, with or without heart of gold. She’s Annie in HER MAN, her runover round heels moving just ahead of the barroom mop, turned back by the U.S. authorities as she attempts to leave her Havana redlight haunts — “Say,” she sasses them, fatalism with hand on hip, “I got a roundtrip ticket.” She’s Bella in MIN AND BILL, a less benevolent waterfront kewpie, wallowing in Wallace Beery’s lap and threatening the happiness of the daughter she abandoned, until Marie Dressler fixes her wagon. She’s Flossie in MAN’S CASTLE, saving a fragile couple from denunciation by a stool pigeon: “Aw, this ain’t murder … this is just housecleanin’.”

But before that, “She Was the Bernhardt of the Klondike,” as Photoplay panted in April 1917. A strapping thirteen-year-old, she played Camille “and all of the sorrowful sisters of her kind,” she told the New York Times, barnstorming up and down the West Coast and as far north as Alaska. “Miss Rambeau was in stock in Los Angeles when that city received its first consignment of raw film” — Photoplay again — “but by the time the stage was being ravished of its stars, she had departed for the east to woo fame in the drama’s capital on Manhattan.” And there she flourished, marrying her playwright and vaudeville partner Willard Mack, gallantly playing her her leading role with backbrace and cane after breaking a leg, divorcing Mr. Mack, marrying the actor playing her son, divorcing him, being named as the “other woman” twice (“MISS RAMBEAU TELLS OF MIDNIGHT RAID; Artist’s Disregard for Conventions Is Defense in Manton Divorce Suit. HER SALLIES DRAW REBUKE Actresses’s ‘Asides’ and Grimaces at Testimony Stir Mirth of Crowd in Courtroom”) — while, almost incidentally, appearing in a series of melodramas that raised Alexander Woolcott’s hackles to high hilarity, “… of late years there has been growing up among our writers for the theatre a sneaking notion that all the people who come to see their shows will not be weak in the head. The authors of ‘The Unknown Woman’ apparently had not heard about this new movement. … there really is no kind of play that is beyond Marjorie Rambeau’s reach. She has such a collection of old stock company tricks that the playwright does not live who could baffle her for a moment. It is also probable that she could rise gloriously and completely to as fine a play as this country is likely to produce in the next ten years, but that remains guesswork.” (What, and share the limelight with an author?)

In 1923, she did play Rosalind.

In 1930, she went back West and brought her plangent, old-stager’s tones to the talkies. She was no ingenue, but, like the actress who could never play Juliet without a touch of the Nurse or the Nurse without a touch of Juliet, she temporized: her Annie’s rolling eyes and beestung lips make her a well-matched sidekick to Helen Twelvetrees’ Frankie; wharfside Bella sports slim pins and a pert come-on.

She played less dualistic parts as well: Lulu in INSPIRATION, adding a schmear of Belle Epoque butterfat to the Deco-ized Daudet of Sapho adapted for Garbo, and delighting Frank O’Hara:

favorites: vichyssoise, capers, bandannas, fudge-nut-ice, collapsibility, the bar of the Winslow, 5:30 and 12:30, leather sweaters, tunafish, cinzano and soda, Marjorie Rambeau in Inspiration

from Biotherm (for Bill Berkson)

In THE RAINS CAME, she’s almost unrecognizable as crisp, social-climbing Mrs. Simon of the American Mission to Ranchipur, dragooning George Brent, with a great crockery smile, into her garden party for “some of the nicer English people.”

In 1953, Paramount took a bicycle pump to Barrie’s Rosalind and blew it into the Ginger Rogers vehicle FOREVER FEMALE. This ALL ABOUT EVE-style Broadway drama opens at Sardi’s during the first act of star Beatrice Page’s (Ginger’s) opening night. A voiceover (not George Sanders, Paul Douglas) introduces various hangers-out at the bar — the producer who turned the play down, the rival playwright, the rejected set designer — before pointing out “an actress who was the Beatrice Page of two decades ago.” There’s Marjorie. As a columnist dashes in for an intermission drink, she asks, exquisitely, “And how was — Miss Page?”

These five words are the only ones she speaks in the entire film. She is not seen again until the last scene, when Ginger has relinquished the ingenue role in her latest play to a youngster and graciously assumed that of the mother. As the ingenue enters Sardi’s to a round of applause, her Broadway assumption is confirmed by the gracious handshake of Miss Rambeau.

By Phoebe Green