Killing Humanitarian Workers as a Strategy: Israel’s Endgame in Gaza

Israel described its clearly deliberate killing of seven humanitarian aid workers on April 1 as a “grave mistake”, a “tragic event” that “happens in war”.

Israel is, obviously, lying. This entire so-called war - actually genocide - in Gaza, has been based on a series of lies, some of which Israel continues to peddle.

For some, in the mainstream media, it took months to accept the obvious fact that Israel has been lying about the events that led to the war and the military objectives of its constant targeting of hospitals, schools, shelters and other civilian facilities.

So, it was only logical for Israel to lie about killing the six internationals, and their Palestinian driver, of the World Central Kitchen (WCK). Notwithstanding an event as atrocious as this, it is implausible for Israel to start telling the truth now.

Luckily, few seem to believe Israel’s version regarding WCK, or its continued massacres elsewhere in Gaza. Israel “cannot credibly investigate its own failure in Gaza,” the US-based NGO said in a statement on April 5.

Hate Poetry: Film Noir’s Final Form

It is the epitome of John Alton's vision of the night. A darkness at once creamy and sour, suffused with smoke, misery, and the jawlines of strange looking character actors.

Alton seems to operate from a principle of pitch darkness, interrupting its velvet flow with the bare minimum of lamps and lightbulbs, creating little pools of illumination amid the pervasive dark that forever seem on the verge of being swallowed up by the great inky amoeba they nestle in.

Is cinematography the sum and substance of Noir — Noir itself — or does baseline hostility to American optimism define a genre benchmark, 1955’s The Big Combo?

Richard Conte’s “Mr. Brown” may spit out his cold Noir sermon — “First is first and second is nobody” — faster than James Cagney, his spiritual forebear in the 1931 pre-Code classic, Blonde Crazy: “The age of chivalry is past — this, honey, is the Age of Chiselry.”

Noir was never fundamentally a genre of shadows, but rather defined itself as a set of underlying attitudes and assumptions — All Talking Pictures were poised, Johnny-on-the-spot, to capture the ensuing madness when the stockmarket crashed in 1929.

It’s tempting to posit this moment of serendipity as both Noir’s metaphysical and political birth, and to suggest that economic calamity and advancing technology met for preordained reasons.

But what sinister apostate canon could possibly have contrived a history of cinema to beat the band where raw indifference is concerned — to produce a Robert Mitchum, whose physical beauty is an effortless nihilist shrug?

Ed Wood Post-Plan 9

Given the number of myths, legends and simple misinformation that’s been spread about Edward D. Wood, Jr. in everything from Michael Medved’s muttonheaded book The Golden Turkey Awards to Tim Burton’s well-meaning fairy tale of a biopic Ed Wood, it seems people have an awful lot to say concerning a man about whom they know very little.. People who have seen at most one or two of his films know the party line, though, and are happy to repeat it ad nauseum. Ed Wood was the worst director who ever lived, and his 1959 sci fi horror conspiracy film Plan 9 from OUter Space the most incompetent movie ever made. Even if they haven’t seen the whole film, even if they couldn’t tell you what the storyline is (yes, there’s a clear story), they can tell you all the reasons why it’s bad. It doesn’t matter that most of the things they list are incorrect—they’ve read them online and heard them from their smug friends, so they must all be in there someplace. For most, it’s all they know and all they need to know. It seems Plan 9 is the end of the story. Maybe after that no one let him make another movie, or maybe he died or something.

But Plan 9 was only Wood’s fourth film. He continued working regularly for almost 20 years after that, right up to his death in 1978. He would direct five more features (only two of which are considered “legitimate”) and write the screenplays for almost two dozen films directed by others.

Sylvia Sidney: Jailhouse Blues

“She always looked like she was gonna cry!” my grandmother would exclaim whenever Sylvia Sidney came up. In her 1930s heyday, Sidney was constantly cast as the victim of circumstance, hovering at the very bottom of the economic ladder, mixed up in crime and usually winding up in or near jail. “I was paid by the tear,” Sidney joked later, and that knowing comment is a measure of just how different she was from her on-screen persona. “My mother and I adored her and her films,” said Tennessee Williams. “She was always so fragile and plaintive. She appeared to need protection. Let me tell you: Sylvia needs no protection. She may look frail, but look in that exquisite purse she carries with her: it contains the balls of thousands of men who annoyed her; the hearts of those who crossed her; and the locations of those who betrayed her.”

Brown Furniture: Notes on Gaza from a Diaspora Cousin

My mother died recently, so I’m still in her home taking care of details. I’m also developing an increasing dedication to several pieces of her furniture: a tall cabinet, the dinner table, and a credenza where we stack the plates. Or maybe I should say, harboring an indecision. These three are a matched set in maybe cherry wood, I’m not sure. I think of them as friends but also wonder if the impulse is too dutiful. Rather than find my own décor, my own life, I’m going to set up a shrine to my parents and just be the secretary of their museum?

What dawns on me later is how fortunate I am: I get to have a full stomach and contemplate furniture, family, and the passage of time from the sprawling comfort of a large gray velour sofa. It’s a luxury to grant the dining table and credenza special powers, making them almost human, bestowing upon them character arcs and stories, practically giving them birth certificates. It’s a way to keep my mother present. And it’s ironic, too. Because the exact opposite is happening to an entire civilian population in Gaza. These past five months, the average Gazan’s personhood has been reduced to furniture.

I have a lot of relatives in Gaza. Some of my cousins are still there. Other cousins, evacuated to Cairo, watched their homes get bombed on television. There’s always been family in Cairo, it’s where my father was born. One of his sisters was a doctor. She married a Palestinian, also a doctor, and they worked in Gaza City, had children and grandchildren, were esteemed for their professional accomplishments. My dad, aunt, and uncle are long gone and I’m relieved they don’t have to witness what is happening, because witnessing is all I can do, and it’s overwhelming.

Doctors’ Wives

In the universe of Frank Borzage’s Doctors’ Wives (Fox Film Corp; 1931), women of a somewhat elevated social status can be cunning, downright predatory. They’re always on the prowl; particularly when it comes to their doctors. Warner Baxter plays Dr. Judson Penning: a big-time, big city surgeon; an aristocrat with a prescription pad, moving shark-like from patient to patient; half his life fearlessly staring into ungodly pits of human matter plopped onto an operating table, the other half at his practice, chained to the fin de siècle ennui and simmering hypochondria of rich, overdressed society dames, with only momentary deference paid to his luckless and long suffering wife (Joan Bennett). Adapted in tear-streaks by Maurine Watkins from a novel by Henry and Sylvia Lieferant, Doctors’ Wives might have yielded, with that premise, a respectable crop of marginally low-down smut had it been made at, say, Warner Bros. with Michael Curtiz or Roy Del Ruth directing – they at least seemed to know what to do with a hopeless assignment when they caught one. Instead it received a painfully earnest recitation at the hands of a time-serving, paradigmatic auteur – an otherwise true and singular voice within the commercial epicenter of this country’s film industry – one that, rather than transcending the handicaps built into the piece, only served to expose the plodding hollowness of its five-and-dime sophistication, replete with a Happy Ending plastered on so blatantly that one might be excused a longing for the gaucheries of simple contrivance. Doctors’ Wives, despite Borzage’s oddly negligible presence behind the camera, is no more than a glorified Programmer; a film that no one ever talks about; that no one with the exception of its initial reviewers has ever really written about. And while it may perhaps be too harsh a sentence to pass on a work so ultimately slight, one cannot escape the judgment that Borzage’s film achieves that most woeful condition an entry in the American canon can fall prey to: It’s the kind of movie that only a hopeless, hero-worshipping auteurist could love … or, conceivably, like.

by Tom Sutpen

The Great Sedition Trial of 1944

In a fireside chat in May 1940, Franklin Roosevelt, who was something of a conspiracy theorist, warned Americans, “Today’s threat to our national security is not a matter of military weapons alone. We know of new methods of attack – the Trojan Horse, the Fifth Column that betrays a nation unprepared for treachery. Spies, saboteurs and traitors are the actors in this new strategy. With all of these we must and will deal vigorously.”

A month later, he signed the Alien Registration Act, aka the Smith Act. It made it a crime punishable by up to 20 years imprisonment to advocate the overthrow of the federal or local governments. It allowed law enforcement to round up not just individuals but whole groups suspected of spreading sedition. To help agents track these pernicious activities and influences, it also required all foreign nationals above the age of 14 to register with the government and be fingerprinted.

As soon as he declared war in December 1941, Roosevelt directed his Attorney General to use the Smith Act to begin rounding up and putting away some of the country’s more vocal and visible Nazi sympathizers. In July 1942 a grand jury in Washington brought indictments against 28 people around the country, all of them irritants to FDR but few of them seeming to pose any real threat to national security. Among them were the German American writer George Sylvester Viereck, who had just been jailed in a separate trial for colluding with the Nazis, and William Griffin, the publisher of the New York Enquirer, accused of colluding with Viereck.

Viereck’s name has been lost to history now, but 100-odd years ago he was the darling of the New York literary set. He was born in Munich in 1884. His father Louis was the illegitimate son of a beautiful actress in Berlin and a royal lover, rumored to be Kaiser Wilhelm himself. Sylvester (he spurned the pedestrian-sounding George) was nicknamed Putty, for Lilliput, because he was so petite.

Five Star Final

No music, just the cries of newsboys. Mervyn LeRoy’s 1931 newspaper melodrama, Five Star Final, begins unconventionally. It’s a Warner Brothers social conscience film, but the grim social commentary is shockingly combined with pre-code spice and wit, as if I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932) and Blessed Event (1932) got fused together in an explosion.

LeRoy directed seven films in 1931, most of them raucous comedies. Here he squeezes every laugh he can from the material, and every tear from the audience – it could get ugly, but somehow doesn’t, except when it wants to.

After the credits we get a classic 30s montage to introduce muckraking New York tabloid The Gazette, featuring a panoply of peroxide switchboard operators, probably all producers’ girlfriends – the star girl, Polly Walters, gets a shot filmed from the switchboard’s viewpoint, nesting amid her wires like a bleached spider.

Raymond Griffith

How did Raymond Griffith get to be so forgotten? I first read about him in Walter Kerr’s The Silent Clowns, and though he sounded fascinating in Kerr’s lambent prose, I found it hard to imagine a really great silent comic having slipped into the land of amnesia so thoroughly. Yet, if you seek out the performer’s work on YouTube (few legitimate avenues offer his movies), you’ll see an extraordinary comedy player.

Griffith is unlike Chaplin, Keaton and Llloyd in that he doesn’t offer an iconic silhouette: his “costume” was a top hat and tux, and his dapper appearance calls to mind France’s great Max Linder. But though Griffith could and did play it straight (notably in Todd Browning’s 1923 White Tiger), he wasn’t seen as a straight actor with a gift for elegant comedy, like Adolphe Menjou. Griffith played a supporting role in the Menjou vehicle Open All Night (1924), and it’s clear he’s a comedy turn, brought in to spice things up with a broader kind of farce. Griffith had, after all, gotten his start at Keystone—where his promotion from gag man to star was swiftly followed by demotion back to the story department, so ill-fitted was his style to the Keystone school of mayhem. Today, Griffith’s few surviving shorts look much more watchable than the hectic knockabout of the typical Sennett programmer. True, they have no structure, but Griffith provides moments of reflection and comic calm amid the maelstrom of brickbats and slaps.

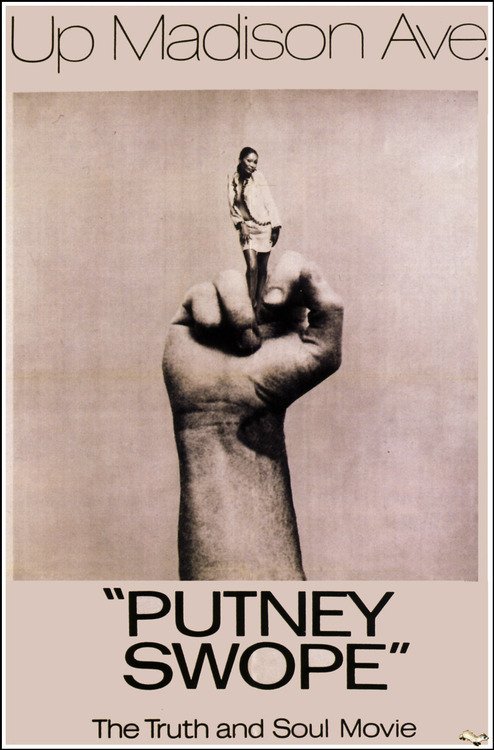

Dope, Dogs& Greasers

Robert Downey, Jr., delivered his first spoken line in a feature-length motion picture at the age of five. He played a puppy in Pound, written and directed by Robert Downey, Sr.

Born Robert Elias in 1935, Downey Sr. was fifteen when he dropped out of the ninth grade and used his stepfather’s surname to enlist in the army. During his time in uniform he reputedly managed to get himself thrown in the brig three times. Once was when he was stationed in Alaska, when he and a buddy, drunk at their radar scopes, faked a Soviet missile attack. By 1960 Downey was in Greenwich Village writing Off-Off Broadway plays. When he read a Village Voice column in which Jonas Mekas declared that anybody could be a filmmaker, he rented a camera and started making low-budget underground films. He hung out with Mekas and other filmmakers at the Charles Theater on Avenue B, where one night a week anyone could screen their work.

From the start he combined avant-garde technique and do-it-yourself impudence with a wacky sense of humor. In the 1964 Babo 73 he cast Taylor Mead as an addled President of the United States, with scenes shot guerrilla-style during a tour of the White House. The 1966 Chafed Elbows combines film and still photos in a way loopily reminiscent of La Jetee to tell the ludicrous tale of Walter Dinsmore, a young man who wanders aimlessly from the New School to the Hotel Dixie, a Times Square flophouse, like a Candide adrift in the Pop Art world. In one scene, a man on the street paints him with the initials AW, declares him a work of art, and escorts him at gunpoint to the Washington Square Gallery, where “you’ll be sold right away, because you’re very pretentious.” In another he records a gibberish pop song, “Hey Hey Hey,” flip side to “Yeah Yeah Yeah.” Tom O'Horgan, soon to be famous (or infamous) for Hair, did the music.

The Sea Speaks: Two Sound Films by Jean Epstein

Jean Epstein was afraid of the sea. It was the kind of fear, he said, that forces a man to do what scares him. On the islands off the coast of Brittany, where he made many of his films starting in the late 1920s, the director and theorist discovered a terrifying ocean and a people for whom death at sea was woven into the pattern of life. Houses on these islands were built from the wood of wrecked ships, and everyone wore black as though ready for mourning. From Finis Terrae (1929) on, Epstein returned again and again to the subjects of lighthouses, storms, boats setting out, boats in peril, islanders waiting for boats to return. It’s a matter of life and death, but it’s also a matter of rhythm and composition, of drama that builds like weather or music.

Mor’vran (1931) and Le Tempestaire (1947) address the same subject and share much of the same imagery, yet the two films have very different effects. Mor’vran (Sea of Ravens) has a documentary detachment, mapping the physical and emotional geography of the Breton islands in a remarkably concise yet encompassing cinematic poem. Le Tempestaire (The Storm Tamer) is narrowly focused on a single incident, and it’s a peerless masterpiece of mood. The films start the same way, with montages of static shots—beached boats, a crucifix against telegraph wires, graves of shipwrecked sailors—but in Le Tempestaire there is immediately an ominous sensation of waiting. It’s created not only by the unearthly music (by Yves Baudrier), but by the timing of the close-ups and the way Epstein plays with the speed of the film. People are frozen at first, as if under a spell, while the sea laps outside.

See Reptilicus and Die

If there are no monster movies on TV, you need to surround yourself with monster movie books, don’t you?

I grew up in an age when there were just three television channels in the UK. Aeon-long days would creak by with nothing on, or at any rate, no deformed freaks of nature menacing the nation, unless you counted Jimmy Savile. Unseen people called schedulers (I have yet to see one), moving in ways more mysterious than God’s, would then put two Ray Harryhausen movies on opposite channels at the same time. And the stronger stuff, the Universal and Hammer films, were always past bedtime, but if I was very lucky, I might be allowed to stay up to see Bela Lugosi or Boris Karloff, my Dad assigned to watch over me and intervene at the first sign of trauma.